Princess Peggy and Solartogs

Meet the Label!

I’ve listed my first thing on eBay in years, and to celebrate, I wrote a long history about it!

Princess Peggy was initially a division of the Chic Manufacturing Co out of Peoria Illinois, a company founded in 1907 as the Chic Apron Co. Chic made wash dresses and children’s bloomers, but in the early days one of the major parts of their business was shop clerk’s black aprons. In 1927, the original founder died, and his son Arnold Salzenstein maybe thought this was a bit boring and directed the business to grow more into patterned and colorful wash dresses as colorfastness of dyes improved. In 1928 the name Princess Peggy was adopted for their $1 house dress line, which would be about $18 today. (No word on whether there was an actual Peggy or if it was just a popular, American-sounding name, which is my guess—Princess Margaret was not born until 1930.)

In the 1930s, they added cotton pajamas, smocks and sportswear to their house dress lineup, as seen in these ads from 1931-32:

In 1938, the Princess Peggy face was added to the advertising. She’s young, Nordically white, blonde, happy, thin but not gaunt, with visibly shiny hair and lips. I won’t spend too much time here, but I find it both interesting and unsurprising that her face reflects the picture of health and beauty as largely unattainable for many Americans during the Great Depression, but the juxtaposition of this face with $1-2 dresses was probably intended to make them feel less cheap. Despite their low price, in the 1940s Princess Peggy dresses came with 2” deep hems and two extra buttons.

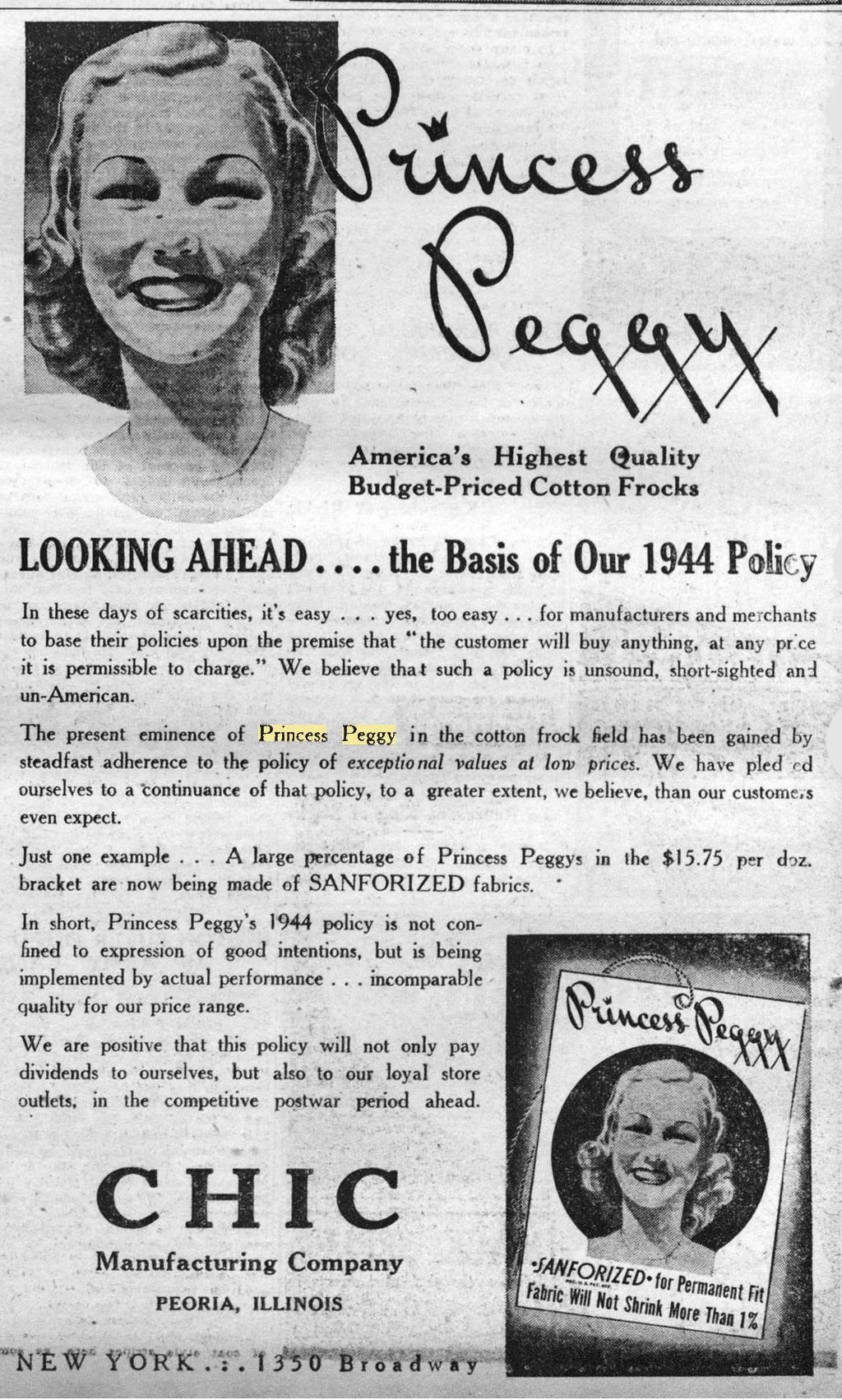

One of the narratives I like to retell when I talk about vintage fashion is how much more expensive it was back then, and how garments at today’s fast fashion prices would be completely unheard of in the 1940s. But cotton wash dresses kind of sit outside of that narrative. Here, Chic reiterates its policy of “exceptional values at low prices” to its trade audience in Women’s Wear Daily, and at $15.75 per dozen, that is an exceptionally low wholesale cost—about $1.30 (about $23 today) per dress. The retail cost for these dresses in 1944, depending on market, was about $1.70 to $2 (about $30-35 today). How much did these dresses cost to make? What were their employees paid?

Chic was a union shop, and so in 1941—the closest year to 1944 we have data for—the ILGWU pay scale provided for a minimum of $14 per week for entry level workers and $16 for skilled workers, but Chic paid a bit more than that at $17-18 per week at their Belleville plant and an average of 44 cents and hour at their Peoria factory, which for a 44 hour week1 is about the same (though many workers would probably be working six, not five, days a week).2 If this was your only job, you’d be making about $70 a month. According to the classified ads in the local paper, you could rent an unfurnished room for about $10 a month, a very small 4-room house for about $20 a month, and a 5-room house for about $35 a month. In today’s numbers, that small house would be about $435 a month, about a third of your earnings of $1480 a month. I’m not accounting for taxes or union dues here, but it gives you a sense of how the numbers would have shaken out. For a single girl with no dependents, no cell phone, internet or television bills, maybe sharing a flat or house with some other workers, this pay would have been tight but pretty livable. She could afford to buy one of the dresses she was making, and it would last a long time.

By the late 1940s, the Princess Peggy label was so successful that it eventually overshadowed anything else Chic was doing, and the corporate name was changed from Chic Manufacturing to Princess Peggy, Inc. They expanded their factories to four locations, making upwards of 200,000 house dresses per month by 1952, when the Solartogs label was trademarked. Initially, the Solartogs mark appeared by itself on labels and advertising without the Princess Peggy moniker, which is interesting given the brand’s success and familiarity among customers, but perhaps Solartogs represented such a departure from the relatively safe house dresses they had been making for decades that they wanted leave themselves room to keep the Princess Peggy name unblemished if the line wasn’t successful, or simply avoid risking customer confusion. At the time, Princess Peggy wash dresses looked like this:

They also were directed at a slightly difference audience. Princess Peggy was available in a wider range of sizes, with some styles going up to a size 44 (I haven’t found a reliable size conversion chart because these aren’t really standardized, but for reference, I am a vintage size 18 or 20 and a modern size 14 or 16). Solartogs started at size 10 (usually a 24” waist) and went up to 18, so potentially aimed at a younger woman.

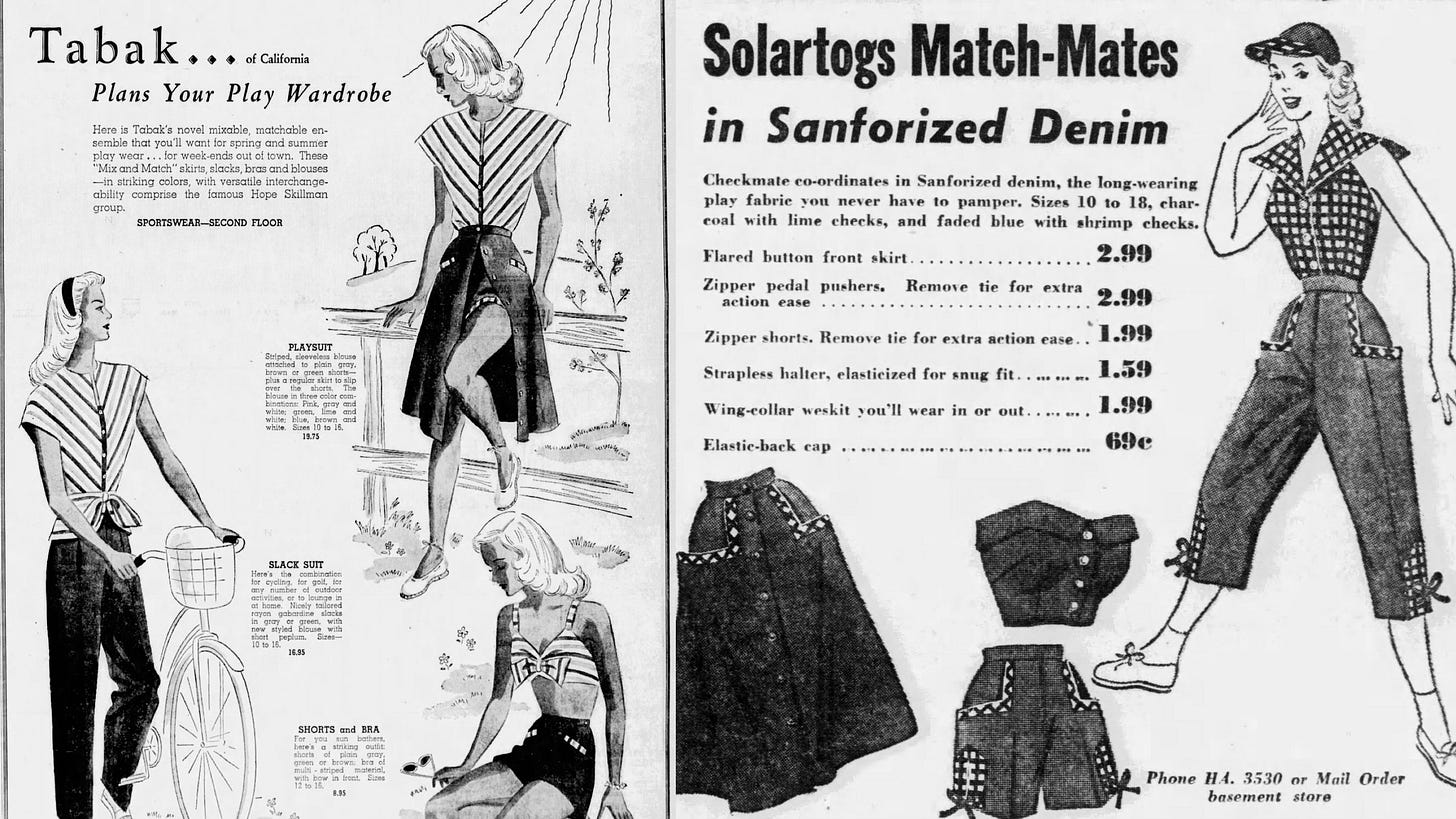

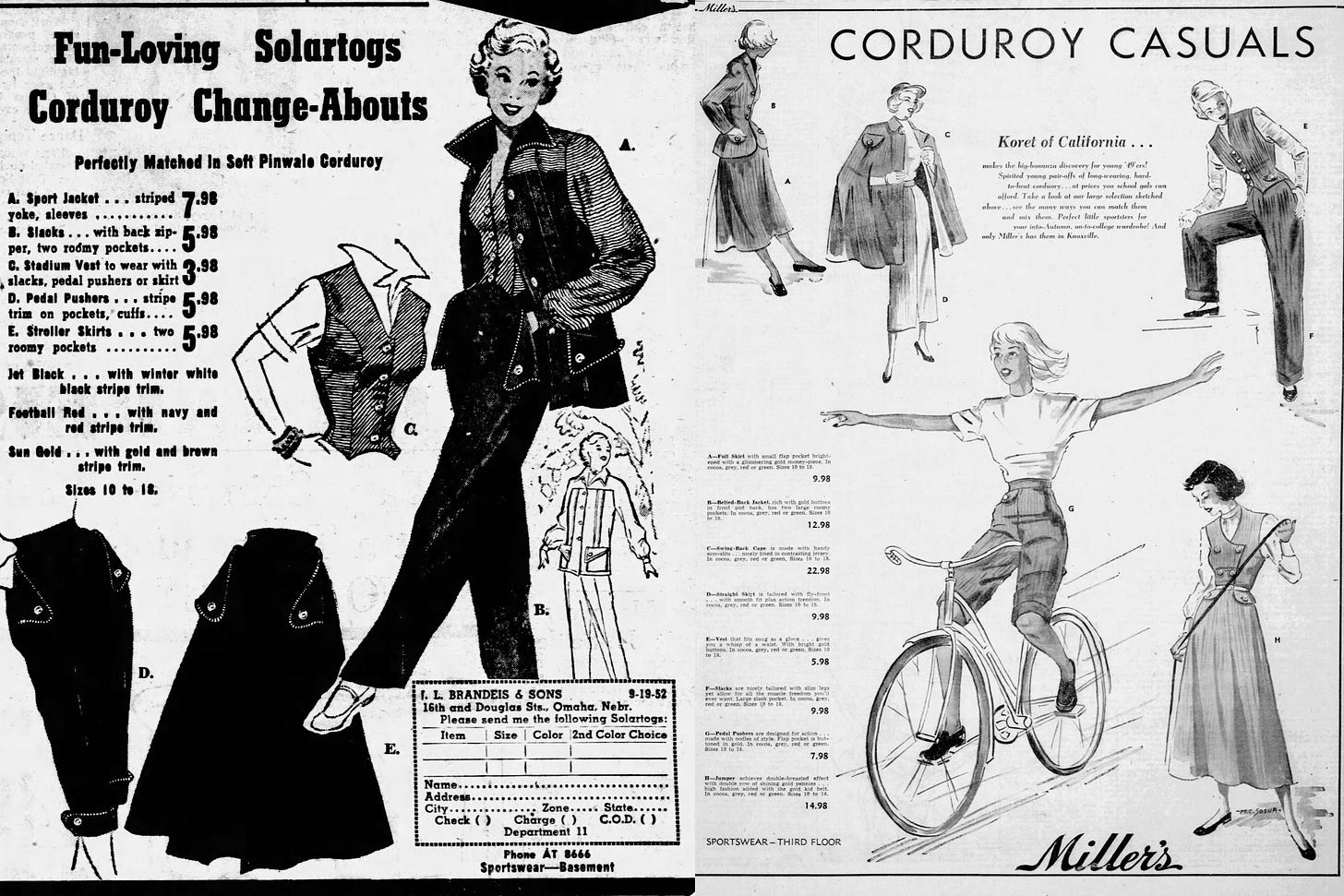

It seems like Solartogs was initially their entry into the popular new-ish casual separates market. California companies like Koret and Tabak were producing coordinating casual clothing that could mix and match to create different outfits with shorts, playsuits, pedal pushers, tops, and skirts. Koret began marketing their “Pair-Offs” in 1948; Tabak had been creating “mix and match” play wardrobes since 1945 and launched the “Tie-ins” line in 1950 with their new designer Irene Saltern. Many of Solartogs’ “Match Mates” look and sound extremely similar to what the California brands were doing.

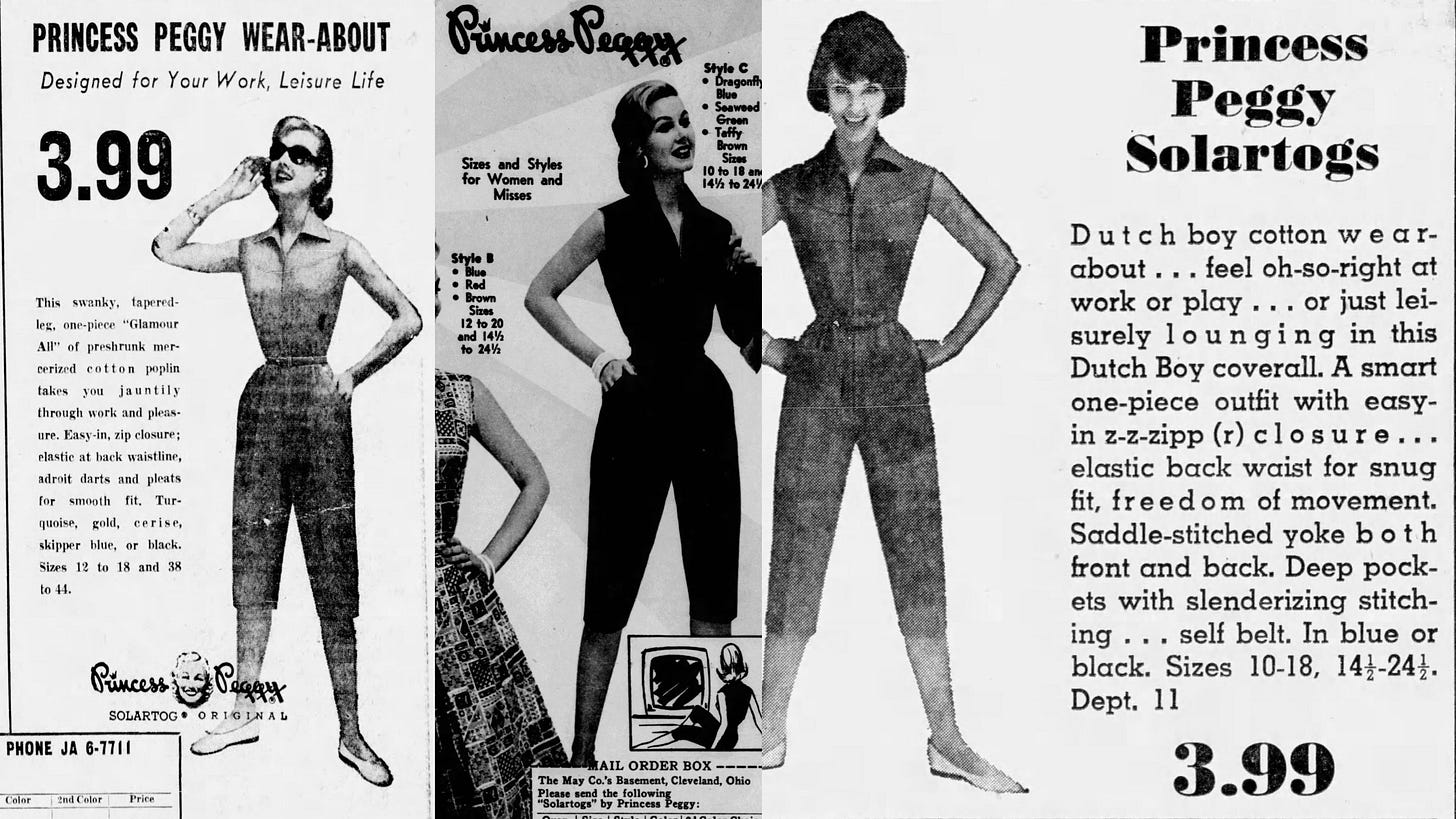

But a core product in Solartogs’ summer collections was this one-piece, zip-front garment with hip pockets and pedal pusher-length short pants that in 1952 did not have a name, but in 1953 was called the Gad-a-bout (which, as a common phrase at the time, was already in use several other companies) and in 1954 became the Wear-a-Bout:

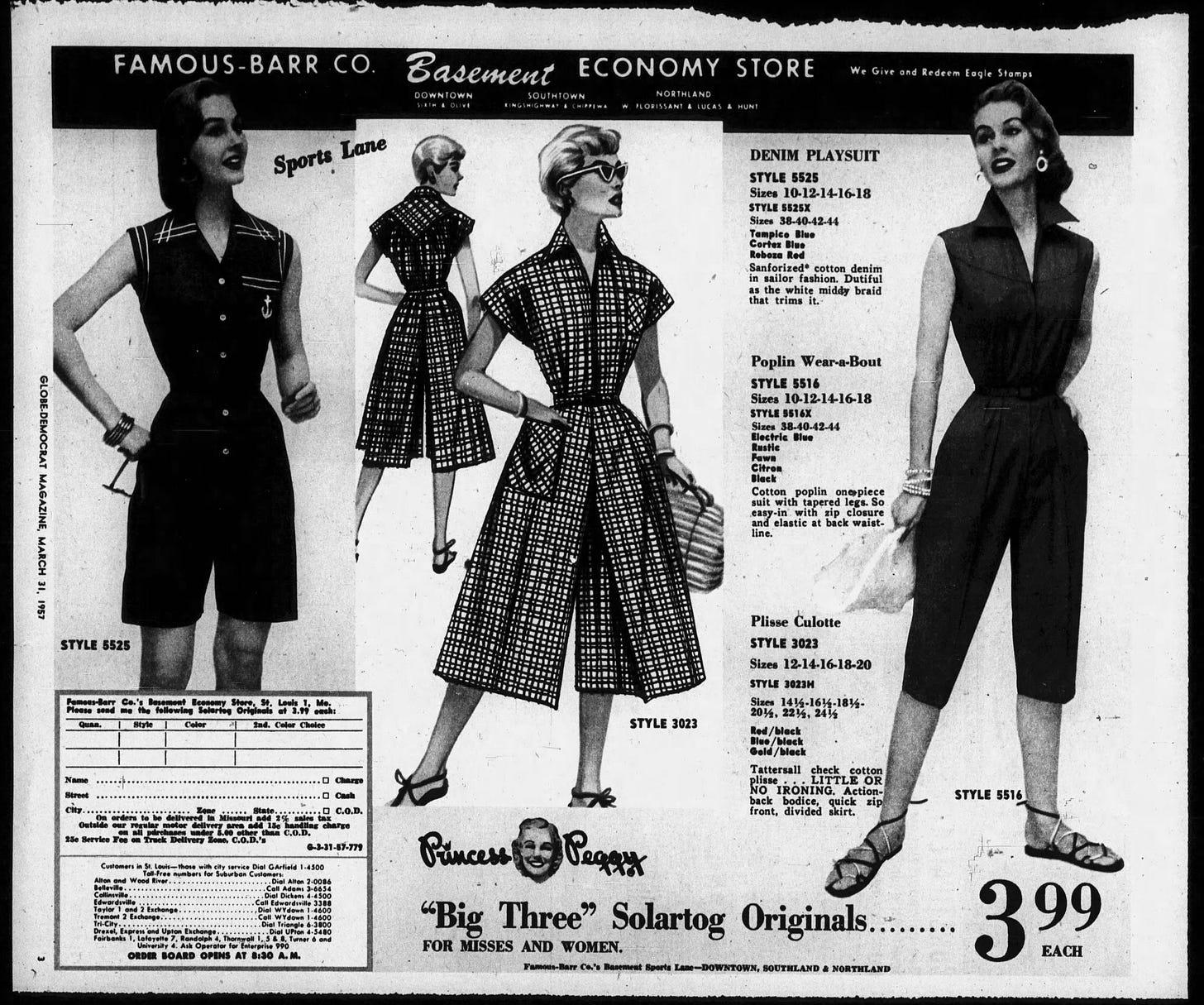

The basic design didn’t change until 1956, and the success of Solartogs must have seemed assured enough for Princess Peggy to start claiming it by then. This design of the “wear-a-bout” stayed pretty constant through the mid-1960s. The below image highlights just how slowly a popular style would change at this time, showcasing the same design from 1956 to 1963:

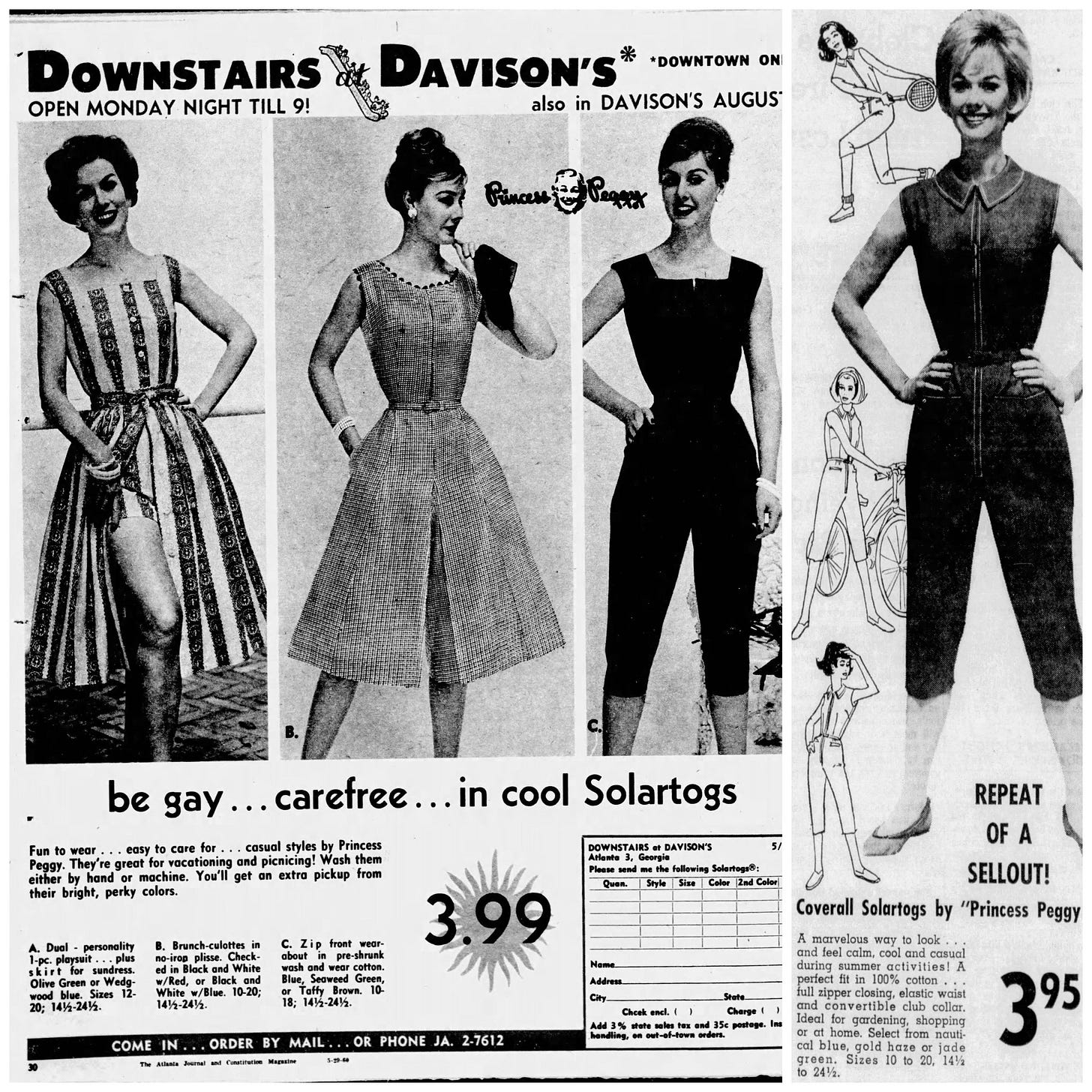

At the same time, there were different versions of a one-piece playsuit that Solartogs released, some with shorts and overskirts, and some with culottes:

The one-piece culottes (above center) were available in “half-sizes”, a euphemism for what we might call plus sizes today. They featured a more generous cut and thoughtful details for movement while still looking tailored. “Youthful styling is a feature of pants sets shown for summer wear in large sizes,” wrote Women’s Wear Daily of this outfit in 1957. “Zipper front closings are popular for they enable easy stepping-into… Demi sleeves are set into an action-back bodice to allow for complete freedom of arm movement.”3 I love a design that allows for freedom of movement and understands that fat people4 might want to wear something youthful.

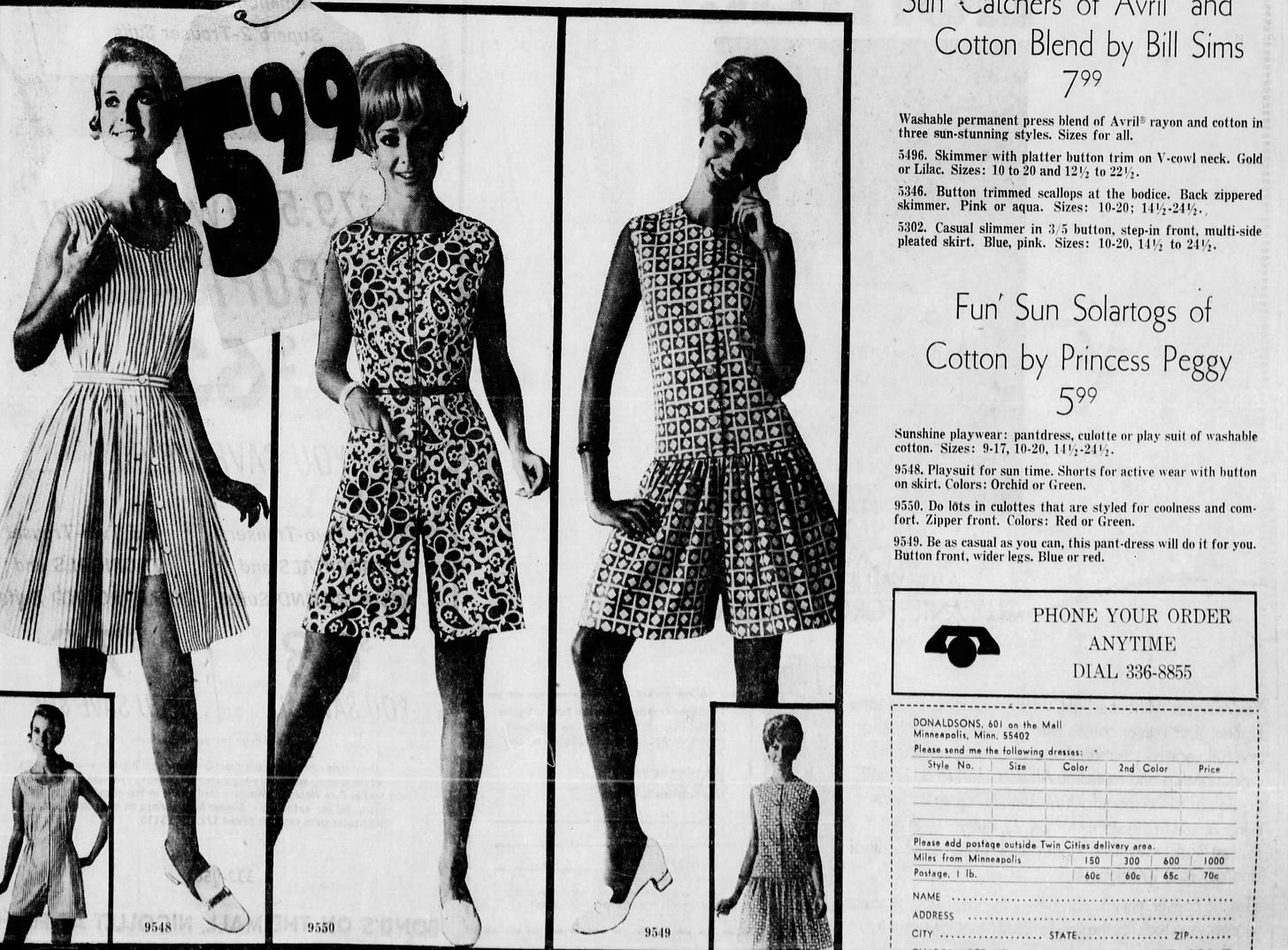

In the 1960s, the “Wear-a-Bout” was also offered in a squared neckline and a rounded collar version, which is the one I have on offer:

Princess Peggy continued to make their one-piece Solartog playsuits through the early 1970s. They filed for bankruptcy in 1974.

And that’s it! A simple garment with a long history. You can check out the listing here, and you can subscribe for more long-winded research.

Factory hours per week varied, but they were likely more than 40. Classified ads at the time advertised up to 48 hours per week. I also looked at the 1950 census for women who I believe worked at the factory at the time (based on their obituaries), which asked the question “how many hours worked in the last week?” I found a range between 40 and 45.

This was taken from an article in the Belleville Illinois Daily Advocate dated June 12, 1941, discussing the opening of a Chic Manufacturing factory in their town.

Culottes, Pedal Pusher Set for the Larger-Sized Customer. Women’s Wear Daily, April 2, 1957.

I use the term “fat” here rather than medically stigmatizing language under guidance from fat activists and writers as a neutral descriptor of body size.

Fascinating. I particularly appreciate your putting the prices in context. I do wonder how dresses that cheap were sustainable given they were paying their workers a living wage. Where were the corners cut?

Hey! Just came across this blog post when I was researching google online on my family’s business! Arnold Salzenstein was my grandpa but he died long before I ever got to meet him. My dad talks a lot about working in that store so wanted to learn more! Such a small world thanks for sharing this deep dive!