Meet a Designer: Helene Scott

Maternity wear, pregnant or not

If you were pregnant in the 1950s, your mother probably came from a generation who did not believe pregnant women—or, to put it more delicately as they might have, expectant mothers—should be seen in public. Attitudes were changing, but this caused some intergenerational friction, as we see in this Ann Landers column from September 25, 1958:

This weirdo attitude came largely from the fact that if a woman is pregnant, that means she has had sex, and this should not be thought about under any circumstances, even if she is married. It is not demure!1 As Leigh Summers writes in Bound to Please: A History of the Victorian Corset —

While middle-class Victorian culture idealized the image of the mother and her post-partum child with almost alarming sentimentality, the pregnant body was considered by polite society to be somewhat repugnant and best kept from view… Even the words pregnant and pregnancy were avoided in polite Victorian company. Pregnancy was, of course, the most obvious demonstration of women’s carnal animality, as well as a reminder of the female body’s predilection for unseemly, squeamish and occasionally painful bodily functions. Consequently, Victorian standards of decency demanded the concealment of the pregnant body and denied any public discussion of either the experience of pregnancy or its accoutrements.

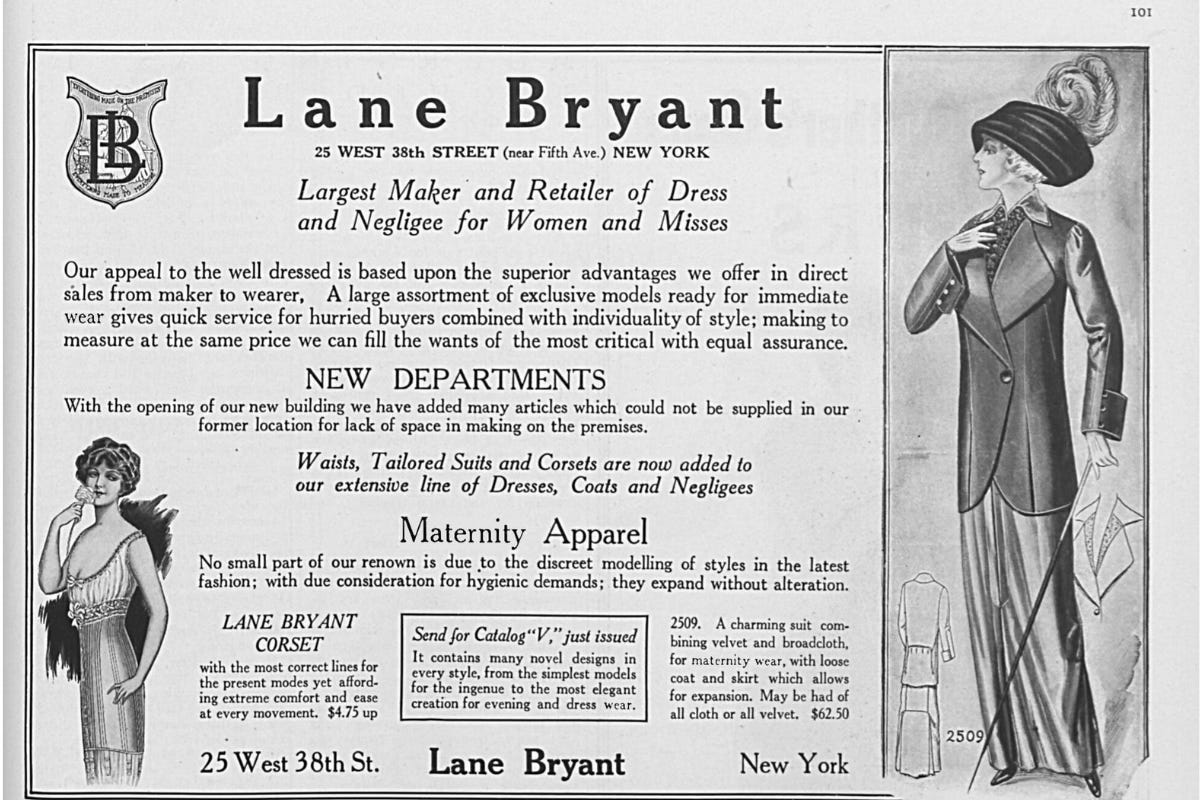

A history about maternity wear and the visibility of pregnant women in public is beyond the scope of this post, but in a nutshell the early part of the 20th century saw women still wearing “maternity corsets” and largely hiding their pregnancies from view for as long as possible.2 In 1910, Lane Bryant advertised their ready-to-wear maternity gowns in Vogue for the first time. Lena’s gowns and suits appeared in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar as appropriate for home or street wear, and they were not inexpensive. For reference, this suit is advertised at $62.50, which would be almost $2000 in today’s dollar.

In the late 1910s and early 20s, dress manufacturers began to realize the potential of this untapped market and started introducing a few maternity pieces at all price points, but Lane Bryant continued to dominate the market for at least a couple decades. In the 1930s, we start to see department stores like Lord & Taylor expanding their maternity departments and more evening wear styles being promoted as well as maternity wear for shorter women, indicating a demand for more ready-to-wear styles for expectant mothers. In 1934, the first expandable dress was designed and patented by a woman named Ora Hunley, who, as far as I can tell, had no formal design training or work experience but did birth at least one child. She licensed the design to three Los Angeles dressmakers, including Marjorie Montgomery of Affiliated Fashionists fame. It featured an abdominal cutout on an underskirt which tied at the waist, hidden by a fuller overskirt, a design that became ubiquitous in the maternity field.

America’s entry into World War II marked a dramatic increase in the national birthrate and a concurrent increase in the demand for maternity wear.3 Maternity manufacturers started to make use of drawstrings and snaps to adjust waist sizes in skirts and dresses, and introduced slacks and sun dresses to their lines. They also had started to utilize cutesy4 names like Blessed Event, Stork-a-Lure, Coming Attraction and Heir Conditioned. Women’s Wear Daily in 1943 reported that “the average wardrobe for today’s mother-to-be is four dresses. This includes one jumper with several blouses, a print and two crepes.”5 At Lane Bryant, you could get a jumper for about $10, blouses at $7 each, a jersey dress for $15 and a crepe for $18.6 If you bought three blouses, your maternity wardrobe would cost about $64, which in today’s dollar is about $1600.

I’m sure that many women preferred to make their own maternity clothes or receive hand-me-downs from friends and family, but the maternity wear industry was nonetheless booming. All over the country, manufacturers were adding maternity lines and stores were adding maternity shops. The demand continued after the war, with larger sizes and slack suits the hardest for stores to keep in stock.7

This is the landscape into which Helene Scott entered when she got pregnant in 1945.

But let’s back up a few years. She grew up Helen Scott in the Winston-Salem area in North Carolina, graduated from high school in 1941 and caught the same wartime wedding fever that seemed to be gripping the country and married her first husband Dallas Cline on Christmas Day of that year. She went to work at Cohen’s Ready-to-Wear shop on West 4th Street, and would later credit shop owner Monte Cohen for teaching her how to walk gracefully and carry herself while modeling clothing. In 1943 her husband was deployed to Italy and wanting to contribute to the war effort herself, Helen began training as a nurse’s aide.

Her first trip overseas would not be as a nurse, however. In the summer of 1944 she left home to go to New York and become a model, and as she told it, about six weeks after walking into the Powers agency she was indeed working steadily as a model in New York.

“Mr. Powers is wonderful and being a model is great fun,” she reported in early 1945. She appeared in a Canadian fur campaign, several ads in magazines like Charm, on a Mademoiselle and a Vogue cover. In June of 1945, she set off for a European USO tour with the Powers entertainment unit, including several other models, a few celebrities, and a nine piece band.8

At some point in this whirlwind start to her career, she got pregnant. Howard Oxenberg was an accomplished swimmer at Yale whose family was in the garment business in New York. During the war he was a swimming instructor for the Navy which exempted him from overseas military service. We don’t know exactly how the two met (one source said “show business”) but it’s likely Helen was already pregnant when she left for her European tour. Their daughter Starr was born in early 1946 and the couple were married a few months later, possibly delayed by the need to secure a divorce from Helen’s first husband, who may have still been overseas.

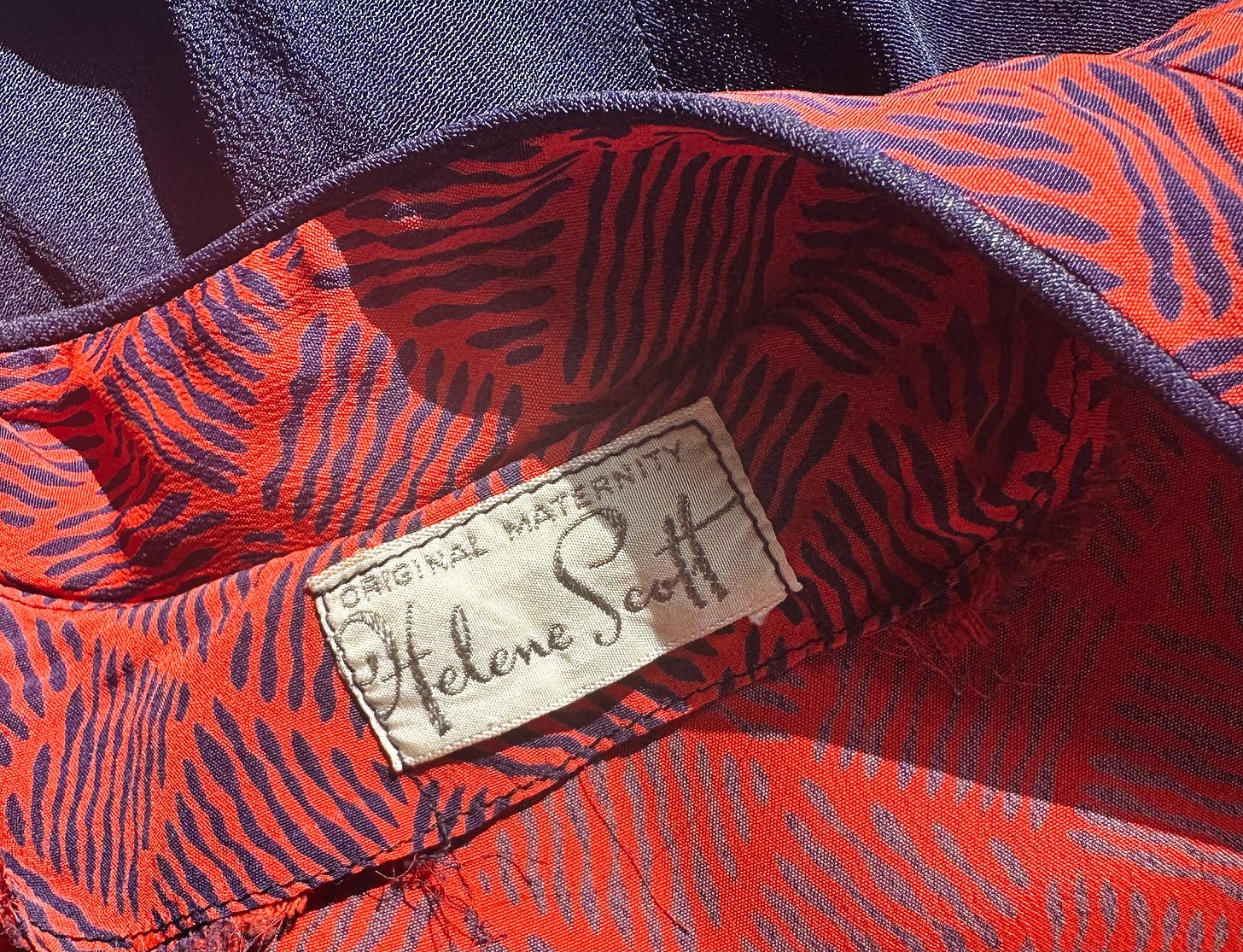

The story goes that Helen, now Helene, designed five or so maternity garments for herself while she was pregnant and her husband’s company used them to start its maternity line, Helene Scott Maternities. It was slow at first, but they decided to take a risk and invest $5000 in a huge fashion show at a fancy hotel (about $85k today and reader, I have never been in the fashion business but why would this cost so much??) and though no one showed up at first, eventually the place was packed and the show was a huge success. “I couldn’t stop designing maternity clothes now if I wanted to,” she said in a 1947 interview. “All my husband’s customers know me as the designer.” She was still modeling, talking about dreams of becoming an actress in Hollywood, as if she didn’t think of the design gig as a permanent one.

But, it turned out, she was good at it. By 1949 Helene Scott Maternities was carried at Lane Bryant stores, and was being advertised nationally.

She often used this collar and fancy buttons, which could be removed with metal shanks like cufflinks for easy washing. She designed suits, sun dresses, swimwear, casual separates, anything you could think of for a maternity wardrobe. This dress would be about $250 in today’s dollar, but its smart design with elasticized waist meant you could belt it (or not!) and wear it forever. Her designs were all smart, and so was she: she talked and listened to women all over the country about what they wanted and needed in maternity clothes, she selected fabrics that would be cost-effective and attractive, she didn’t include complicated fasteners that would be hard to do up yourself.

Helene continued to book modeling gigs while designing for the company and traveling around the country doing trunk shows and talking to buyers and customers. She almost always had live-in help and childcare and was open about the difficulty of maintaining a career and being a mother. “I wonder about these women who can be a mother, gardener, homekeeper, clubwoman and career woman all in one,” she told the Winston-Salem Journal in October of 1952, three years after the birth of her second child. “I don't see how it's possible to do more than work at a career all day. I would probably like to cook if I ever had time to learn. I feel frustrated a lot of the time, too. I think maybe I should be at home learning the housekeeping business, but at home, I keep thinking I should be back in the city at work.” She was articulating something I think most women (even me, who has no children) still feel, over 70 years later.

But after nearly a decade, things began to fall apart in a public way. Helene asserted that she began asking for an accounting of the business and wanted to know what her stake was financially for her labor over the years and where her money was, and that her husband and his family brushed her off. She claimed that he was emotionally and sometimes physically abusive, once refusing to let her go to a hospital while they were traveling for work when she had was sick with a kidney ailment, and that he openly cheated on her with buyers and with their maid. For his part, Howard denied any infidelity and often justified his behavior with familiar versions of “but she (fill in the blank)!”

In July of 1955, she had a flight booked to the Virgin Islands for a much-needed vacation. The night before she was to leave, Howard took her out to a sort of farewell dinner, but instead of heading back home or to the airport, he had her involuntarily committed at the River Crest Sanitarium in Queens under the care of one Dr. Samuel Stoltz, who she says conducted no examination but relied on false statements by her husband to have her committed. Though she was released after only a few weeks and they stayed together for the next year, in July of 1956 Helene sued for divorce, and in 1957 she filed an action against Howard and his family over the commitment and stolen wages, asking for $2 million in damages and $500,000 in wages. The suit dragged on with he said/she said in the papers, and I can't imagine what a horrible time this must have been for their kids, who were around 12 and 8.

(This is a personal aside, but if it sounds like I am biased toward Helene, I am. I once had a guy friend who would get SO MAD if I questioned his retelling of a story about something that happened between him and his girlfriend, saying some version of “you’re siding with her just because she’s a woman” or “it wouldn’t even matter what she did because you’re always going to side against me.” I could not get it through to him that it was much more nuanced than that, that I was tending to believe her because I had been her, because I know how shitty and confusing this guy’s behavior could be because I had been witnessing it from him and other men for years, men who had never been held accountable and honestly did not feel they were doing anything wrong or unjustified, and insisted on whining about how they were being treated when in reality, they were so focused on themselves that they could not see how their behavior was affecting their partners, who, as girls, had been raised and conditioned in a completely different way than they had. It’s the thing where if a woman sets a boundary, a man might get his feelings hurt, and the conversation then has to be about how offended he is. This is a total digression, and it doesn’t even matter because ultimately the courts believed Helene had been subject to extreme cruelty and she was granted her divorce in 1958, in a settlement which included the house, plus alimony and child support.)

For the wages, Howard and his family alleged that there had never been any employment contract so she was entitled to nothing, but in 1960 she was ultimately awarded $81,000. It was far less than what she’d asked for but still about $875,000 in today’s dollar. On the commitment charges, she settled with the family out of court for $120,000 and though she pursued the $2 million action against the sanitarium’s doctor, the outcome was not reported.

Howard, then 41, eloped with the 24-year-old princess of Yugoslavia after meeting on the ski slopes of St. Anton in 1961 and, seeing a decline in the birth rate, started a budget (non-maternity) clothing line called Cobbs Corner the same year. He was an early proponent of fast fashion and saw the financial potential of selling a lot of cheap clothes:

“Customers will make multiple purchases out of season if you give them areas of convenience, styling and pricing. They do buy emotionally and we work on the basis of emotional impulse selling… Instead of buying one dress for $35, girls will buy four of ours. The dress market can only motivate this kind of customer by giving her ‘disposable dresses.’ A linen dress looks like hell the next year anyway, and if it’s a $50 dress, the girl hates to throw it away.”9

She certainly does. When asked about his target market for this line, he grinned and said “We’re going after a certain group at Cobbs Corner. If I’m going to have a target, let it be beautiful girls.” Sir, are we still talking about Cobbs Corner? Because in 1967 he and Princess Elizabeth divorced and in 1969 he married Lehman heiress Maureen McCluskey, who was graduating from Vassar the same year that Howard’s oldest daughter was graduating from high school. He married at least twice more, the last time in 1995 to a woman who was fifty-one years younger than him.

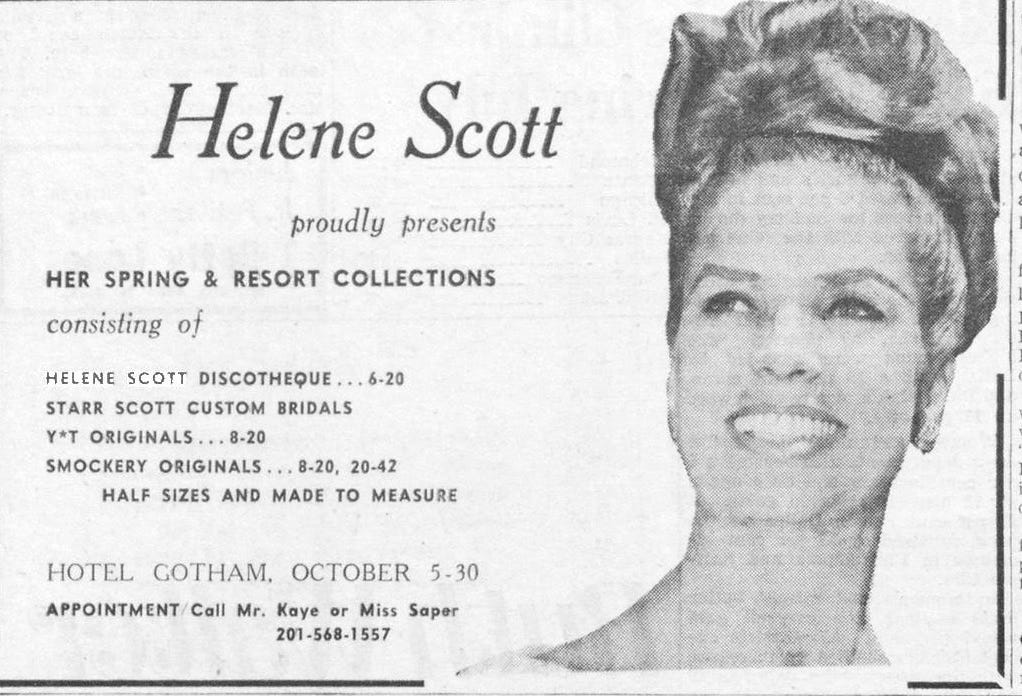

For as much as Howard Oxenberg was covered in the papers, Helene was just the opposite. It’s unclear how long she continued to design for the Oxenberg businesses, which by 1959 included her Starr Separates line, but it seems like by 1964 she was doing some independent designing that had nothing to do with Oxenbergs or maternity.

After this, the research trail goes cold, which is probably a good thing since I’m almost at the limit for one email and I have dug into this woman’s life quite enough. I’m just so impressed with her that she had the wherewithal to stand up to this guy and his family and win, and I love that I get to have a piece of her history in my closet.

I started writing this months ago before I knew this was an internet thing

For working class women, this was as much practical as it was social, as once it was known you were pregnant, you would immediately lose your job.

A page from the maternity section in Women’s Wear Daily, February 24, 1943 reported that maternity wear sales were up 30-40% over the previous year due to the increase in wartime marriages and births. We tend to think of the baby boom as happening after the war, but data clearly show it began several years earlier. They also indicate that older mothers are buying more maternity wear, increasing the demand for larger sizes that weren’t selling in previous years.

see note 1

This comes from the same February 24, 1943 article as above.

Baby Talk...Maternity Fashions Take a New Lease on Life. Vogue, November 1, 1943.

Women’s Wear Daily, May 7, 1946.

Even though the war in Europe was over, there were still over 3 million Americans stationed there, and they would not begin to be shipped home until late June. From VE Day until September 1945, when Japan surrendered, only about a third of Americans had been sent home, so there was still some entertaining to do.

This is from a Women’s Wear Daily article and honestly it irritated me so much I closed the tab without looking at the date. He also once said to a reporter about how his social set was doing during difficult economic times in 1975: “The poor have always been poor. Others like us have always been lucky. We are not in a depression. They are, and probably always will be.” That’s from the New York Daily News, Feb 23, 1975.

I love how I had never heard of Howard Oxenburg before reading this essay and now I hate him with every fibre of my being. For I have also had way too many encounters with his entitled, oblivious, casually malicious kind. Blergh. Here's hoping Helene prospered.

This was fascinating. Thank you.

1. Your personal aside in this was spot on.

2. This entire story is fascinating.

3. Hell yes, Helene. Make him pay. 💰 💪

Great piece!!