In the early 1930s, the garment industry in Los Angeles was beginning to find its footing. Dozens of small factories were operating all over the city, mostly downtown, using a labor force made up primarily of immigrants, mostly women of all ages from Mexico, along with some Italians, Russian Jewish girls, and some Black women and Dust Bowl refugees. Los Angeles was a non-union town, an “open shop” town, meaning that companies could not discriminate against workers as long as they did not unionize. They even had an anti-picketing law on the books since 1911—the same year as the Triangle Shirtwaist fire. The New York-based International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) sought to disrupt the open shop policy in Los Angeles in 1933 by sending Rose Pesotta, a former garment worker herself and also a Jewish immigrant, to help the workers unionize.

Here, women work at the Patsy Jane Frock company in Los Angeles in what looks like the late 20s or early 30s. We don’t know exactly what these women were earning, but we do know that even after the state minimum wage was raised to $16/week in 1920, many women garment workers continued to earn less, particularly as compared with workers in San Francisco who were already much better organized.1

So when Rose Pesotta set out from New York to organize these workers, it may have seemed like a near-impossible task. The cultural and practical differences between the New York industry, with its leadership overwhelmingly comprised of older Jewish men whose expertise was in the East Coast coat and suit trade, and the California industry, with its emerging focus on lightweight cottons and sportswear made primarily by women whose backgrounds they did not make any real effort to understand, created severe tensions that were often simply dismissed by the men in charge of the union. Paradoxically, most of these men believed that women were impossible to organize because their primary roles as caretakers and housekeepers would make their employment inconsistent. Some believed that women shouldn’t be part of the labor force at all, either because jobs during the Depression were so scarce that all should go to men, or because the mere presence of women in the industry meant that pay rates for men were lower than they otherwise would be. Or, a few thought it was just because women should be making and caring for children and the home, full stop.

In this hostile climate, it’s possible that Pesotta was one of the few people who could have successfully helped local women unionized Los Angeles garment shops. She came to New York from Ukraine when she was seventeen, in part to escape the probability of an arranged marriage and subsequent housewifery. She followed her sister, who was already working in a shirtwaist factory, and joined Waistmakers’ Local 25 during the First World War. Local 25, unlike other ILGWU chapters, was mostly run by women activists in a delegate structure, providing comprehensive education for its members on health, politics, economic matters, leadership and union procedure (until it was later forced to merge with a chapter dominated by men; Local 25 really is a topic in itself). She took classes at Bryn Mawr and Brookwood Labor College, advocated for free love and anarchism, and continued to work in union organizing.2 She understood the challenges of the Los Angeles garment workers because she had been one, and had been fired and blacklisted for union activity.3 This experience earned her some credibility among the workers, who petitioned the ILGWU in New York to send Pesotta back as a union representative and help them organize. Despite the union’s general attitude that Mexican women could not be organized, president David Dubinsky agreed to put her on a plane in September of 1933.

The Los Angeles labor market at the time was what could be described as predatory, or at least opportunistic: the transient population, lured by promises of year round sunshine and abundance, found on arrival their employment options limited and competitive. Employers intentionally hired and fired staff in part to create an unstable work force that would make organization difficult, and in part because the work wasn’t steady. “If a rush order for a few dozen dresses came in—for this was largely a short-order industry serving the local market—certain firms put out a Help Wanted sign, bringing in all the workers that could possibly be placed. As soon as the order was filled, they would be laid off,” wrote Pesotta in her 1945 autobiography Bread Upon the Waters.

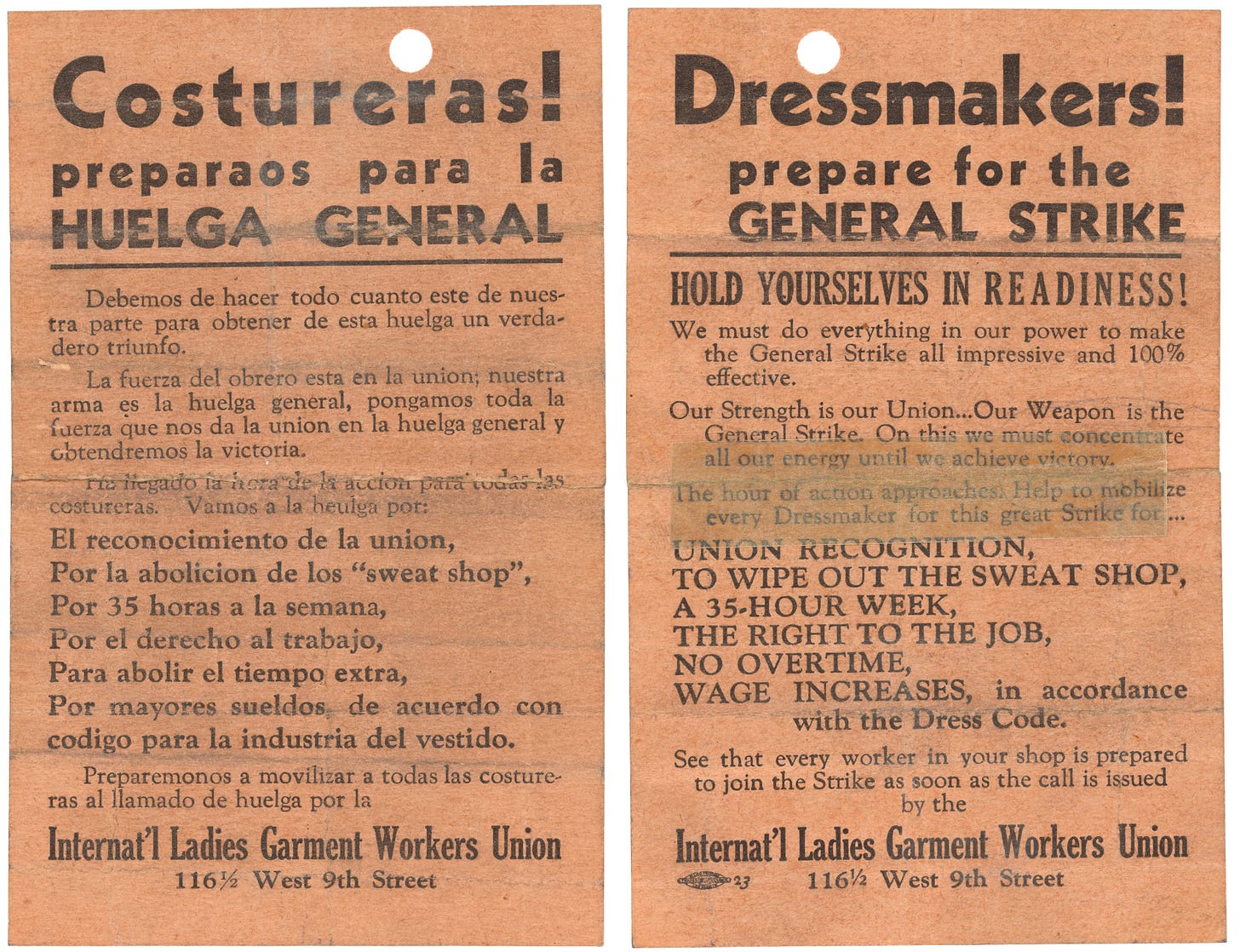

To help reach the Mexican workers, Pesotta coordinated with a local Spanish language radio station to broadcast every evening at 7 to talk about the union. She and her staff organized a semi-weekly newspaper in both Spanish and English, and issued leaflets and posters in both languages as well. Pesotta visited workers in their East Los Angeles neighborhoods and on Olvera Street. In late September, they felt they had enough momentum to call for a strike.

The newly organized workers set forth their demands to management, including recognition of their union, a 35 hour work week, adherence to federal minimum wages (the National Recovery Act Dress Codes set forth a higher minimum wage as part of the New Deal), no home work (they were frequently required to take work home without additional pay) and punching time cards only when leaving or coming to work. Several hundred workers joined the new Dressmakers Local 96, and they endorsed a city-wide strike, which began on October 12, 1933. More than 3000 workers registered for the strike, including dressmakers and local coat and suit workers that were not part of the union but had their own grievances to settle.

But just five days later, the coat and suit faction signed a separate agreement, undermining the dressmakers’ position. They continued to picket, many were arrested, and ultimately the strike ended on November 6 with several of their demands met—in theory, they were to receive the hours and wages they’d asked for, but in reality these provisions weren’t enforceable. Overall, the results were mixed, but the event is widely recognized as an important labor milestone, in part because it was the first strike largely organized and executed by Mexican women.

“Thus, although the 1933 strike produced few material gains, it did give many dressmakers an opportunity to develop their organizing skills. Their strength, solidarity, and militancy contradicted the widespread belief that Latina dressmakers could not be organized. However, not even Pesotta’s enthusiasm could force the male Los Angeles leaders of the ILGWU to give these newly seasoned women control over the actual running of the enlarged union. Of the nineteen officials elected to constitute Local 96’s new leadership, Mexican women help only six positions on the Executive Board. None of them was elected to high office.”4

That would not happen until the 1970s.

Next time, we’ll look at the 1941 strike and how the industry changed in the intervening and following years.

Rebecca J. Mead (1998), "Let the Women Get Their Wages as Men Do": Trade Union Women and the Legislated Minimum Wage in California. Pacific Historical Review, Aug., 1998, Vol. 67, No. 3, pp. 334-346.

John H.M. Laslett (1993), Gender, Class or Ethno-Cultural Struggle? The Problematic Relationship between Rose Pesotta and the Los Angeles ILGWU. California History, Vol. 72, No. 1, Women in California History (Spring, 1993), p. 23.

Rose Pesotta, Bread Upon the Waters, ed. John Nicholas Beffel (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. 1944).

Laslett. Gender, Class or Ethno-Cultural Struggle? The Problematic Relationship between Rose Pesotta and the Los Angeles ILGWU, p. 31.

Really interesting read! It feels helpful to know that even though they weren’t completely successful with their strike it was still note worthy and made progress.